Bio & Information

Satsuma Bio

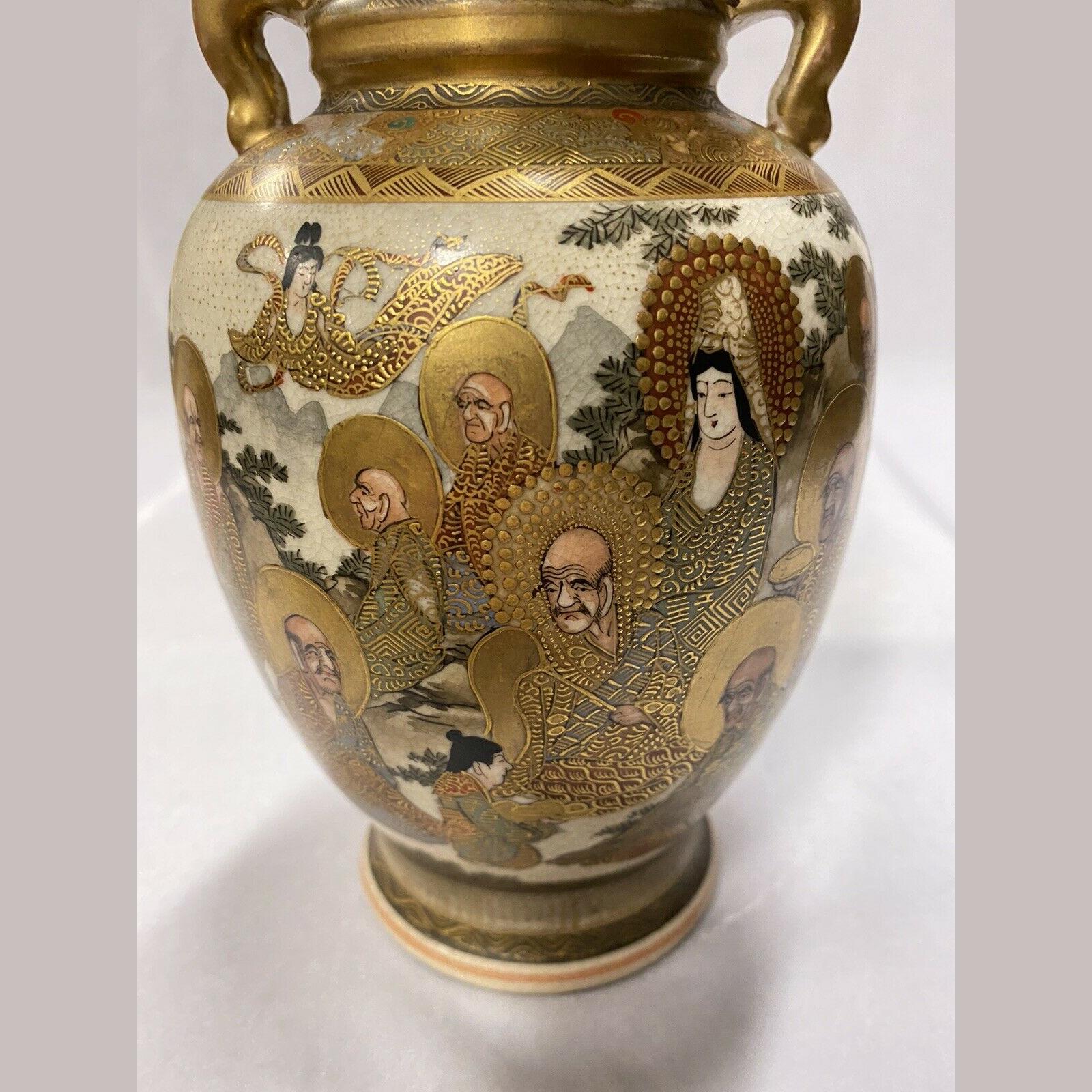

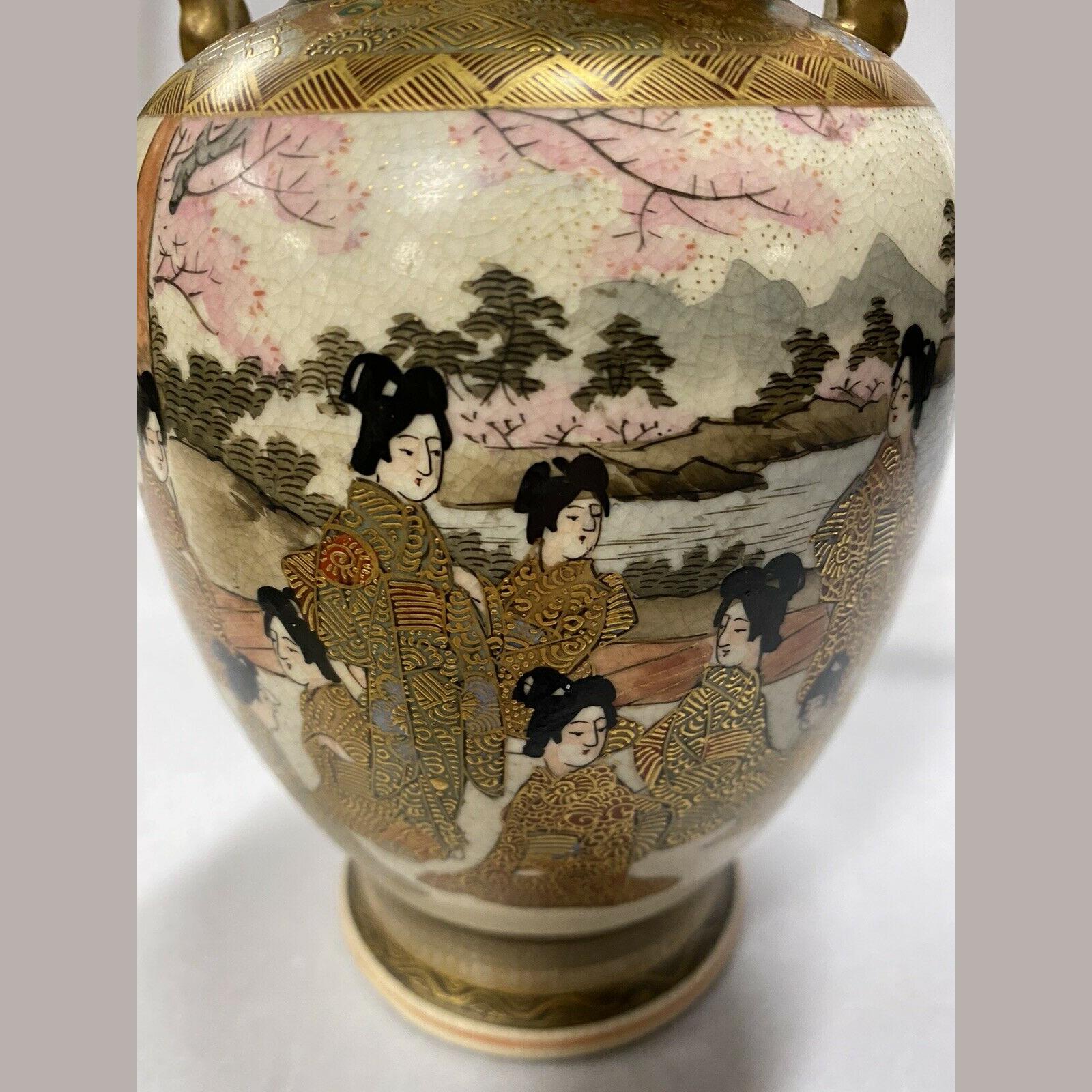

Satsuma ware is a type of Japanese pottery originally from Satsuma Province southern Kyūshū Today it can be divided into two distinct categories the original plain dark clay early Satsuma made in Satsuma from around 1600 and the elaborately decorated export Satsuma ivory-bodied pieces which began to be produced in the nineteenth century in various Japanese cities By adapting their gilded polychromatic enamel overglaze designs to appeal to the tastes of western consumers manufacturers of the latter made Satsuma ware one of the most recognized and profitable export products of the Meiji period

Satsuma ware dates its appearance to the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century The Satsuma region was ripe for the development of kilns due to its access to local clay and proximity to the Korean peninsula In 1597–1598 at the conclusion of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s incursions into Korea – Korean potters were forcefully brought to Japan to kick-start Kyūshū’s non-existent ceramic industry These potters eventually mainly settled in Naeshirogawa and Tateno which were to become the hub of the local pottery industry Satsuma ware dating up to the first years of the Genroku era (1688–1704) is often referred to as Early Satsuma or ko-satsuma The oldest remaining examples of Satsuma are stoneware made from iron-rich dark clay covered in dark glaze Prior to 1790 pieces were not ornately decorated but rather humble articles of folk-ware intended for practical everyday use in largely rustic environments or the tea ceremony Given that they were “largely destined for use in gloomy farmhouse kitchens” potters often relied on tactile techniques such as raised relief stamp impressions and clay carving to give pieces interest From around 1800, brocade nishikide painted decoration began to flourish including a palette of “delicate iron-red, a glossy blue a bluish green a soft purple black and a yellow very sparingly used” A slightly later innovation added painted gilding to the brocade kin nishikide The multi-coloured enamel overglaze and gold were painted on delicate ivory-bodied pieces with a finely crackled transparent glaze The designs—often light simple floral patterns—were highly influenced by both Kyoto pottery and the Kanō school of painting resulting in an emphasis on negative space Many believe this came from Satsuma potters visiting Kyoto in the late seventeenth century to learn overglaze painting techniques The first major presentation of Japanese arts and culture to the West was at Paris’ Exposition Universelle in 1867 and Satsuma ware figured prominently among the items displayed The region’s governor the daimyō understood early the economic prestige and political advantages of a trade relationship with the West In order to maintain its connection with Satsuma for example Britain offered support to the Daimyō in the 1868 rebellion against the shogunate The Paris Exposition showcased Satsuma’s ceramics lacquerware wood tea ceremony implements bamboo wicker and textiles under Satsuma’s regional banner—rather than Japan’s—as a sign of the Daimyō’s antipathy to the national shogunate Following the popularity of Satsuma ware at the 1867 exhibition and its mention in Audsley and Bowes’ Keramic Art of Japan in 1875 the two major workshops producing these pieces those headed by Boku Seikan and Chin Jukan were joined by a number of others across Japan “Satsuma” ceased to be a geographical marker and began to convey an aesthetic By 1873, etsuke workshops specializing in painting blank-glazed stoneware items from Satsuma had sprung up in Kobe and Yokohama In places such as Kutani Kyoto and Tokyo workshops made their own blanks eliminating any actual connection with Satsuma From the early 1890s through the early 1920s there were more than twenty etsuke factories producing Satsuma ware as well as a number of small independent studios producing high-quality pieces Eager to tap into the burgeoning foreign market producers adapted the nishikide Satsuma model The resulting export style demonstrated an aesthetic thought to reflect foreign tastes Items were covered with the millefleur-like ‘flower-packed’ hanazume pattern or ‘filled-in painting’ nuritsubushi They were typically decorated with “‘quaint’ … symbols such as pagodas folding fans or kimono-clad [females]” Pieces continued to feature floral and bird designs but religious mythological landscape and genre scenes also increased There was new interest in producing decorative pieces (okimono) such as figurines of beautiful women (bijin) animals children and religious subjects The palette darkened and there was generous application of moriage raised gold